HELEN DENERLEY | Salvage: a solo exhibition of new work by Helen Denerley

HELEN DENERLEY | Salvage: a solo exhibition of new work by Helen Denerley

- Works

- Overview

- Publications

- News

- Installation Views

-

Share

- X

- Tumblr

-

Helen DenerleyInfinity Column, 2023fire extinguishers and boiler expansion tanks6.5m high%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EInfinity%20Column%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Efire%20extinguishers%20and%20boiler%20expansion%20tanks%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E6.5m%20high%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyInfinity Column, 2023fire extinguishers and boiler expansion tanks6.5m high%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EInfinity%20Column%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Efire%20extinguishers%20and%20boiler%20expansion%20tanks%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E6.5m%20high%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGiant spider, 2023combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high£ 33,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGiant%20spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecombine%20harvester%20dividers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egas%20guns%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etanks%20and%20barbeque%20lid%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.3m%20high%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGiant spider, 2023combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high£ 33,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGiant%20spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecombine%20harvester%20dividers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egas%20guns%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etanks%20and%20barbeque%20lid%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.3m%20high%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyMale orangutan, 2023120cm (h) x 90cm x 45cmold British motorbikes, tilly lamp and scaffold parts£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMale%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%2090cm%20x%2045cm%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbikes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etilly%20lamp%20and%20scaffold%20parts%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyMale orangutan, 2023120cm (h) x 90cm x 45cmold British motorbikes, tilly lamp and scaffold parts£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMale%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%2090cm%20x%2045cm%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbikes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etilly%20lamp%20and%20scaffold%20parts%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyMother and baby orangutan, 2023old British motorbike frames, brake shoes, scaffolding parts, bolts, bells.66cm (h) x 114cm x 74cm£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMother%20and%20baby%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbike%20frames%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebolts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebells.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E66cm%20%28h%29%20x%20114cm%20x%2074cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyMother and baby orangutan, 2023old British motorbike frames, brake shoes, scaffolding parts, bolts, bells.66cm (h) x 114cm x 74cm£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMother%20and%20baby%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbike%20frames%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebolts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebells.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E66cm%20%28h%29%20x%20114cm%20x%2074cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyHaiku sphere, 2023mild-steel rod100cm x 100cm x 100cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EHaiku%20sphere%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emild-steel%20rod%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E100cm%20x%20100cm%20x%20100cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyHaiku sphere, 2023mild-steel rod100cm x 100cm x 100cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EHaiku%20sphere%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emild-steel%20rod%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E100cm%20x%20100cm%20x%20100cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGoat i, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers73cm (h) x 103cm x 32cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E73cm%20%28h%29%20x%20103cm%20x%2032cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGoat i, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers73cm (h) x 103cm x 32cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E73cm%20%28h%29%20x%20103cm%20x%2032cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGoat ii, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers72cm (h) x 111cm x 38cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E72cm%20%28h%29%20x%20111cm%20x%2038cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGoat ii, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers72cm (h) x 111cm x 38cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E72cm%20%28h%29%20x%20111cm%20x%2038cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyFound object chess set, table and chairs, 2023drills, meat-grinders and agricultural scrapKing 47cm high, board 120cm x 120cm£ 15,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EFound%20object%20chess%20set%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etable%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Edrills%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emeat-grinders%20and%20agricultural%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3EKing%2047cm%20high%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eboard%20120cm%20x%20120cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyFound object chess set, table and chairs, 2023drills, meat-grinders and agricultural scrapKing 47cm high, board 120cm x 120cm£ 15,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EFound%20object%20chess%20set%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etable%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Edrills%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emeat-grinders%20and%20agricultural%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3EKing%2047cm%20high%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eboard%20120cm%20x%20120cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLurcher ii, 2019scrap metal133cm x 72cm (h) x 25cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELurcher%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2019%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E133cm%20x%2072cm%20%28h%29%20x%2025cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyLurcher ii, 2019scrap metal133cm x 72cm (h) x 25cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELurcher%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2019%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E133cm%20x%2072cm%20%28h%29%20x%2025cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023agricultural parts, brake shoes and scythes110cm (h) x 143cm x 69cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scythes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E110cm%20%28h%29%20x%20143cm%20x%2069cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023agricultural parts, brake shoes and scythes110cm (h) x 143cm x 69cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scythes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E110cm%20%28h%29%20x%20143cm%20x%2069cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyCaliper Moth, 2023calipers, brake discs, clutch plates and silencer113cm (h) x 248cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ECaliper%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecalipers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20discs%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eclutch%20plates%20and%20silencer%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E113cm%20%28h%29%20x%20248cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyCaliper Moth, 2023calipers, brake discs, clutch plates and silencer113cm (h) x 248cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ECaliper%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecalipers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20discs%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eclutch%20plates%20and%20silencer%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E113cm%20%28h%29%20x%20248cm%3C/div%3E

-

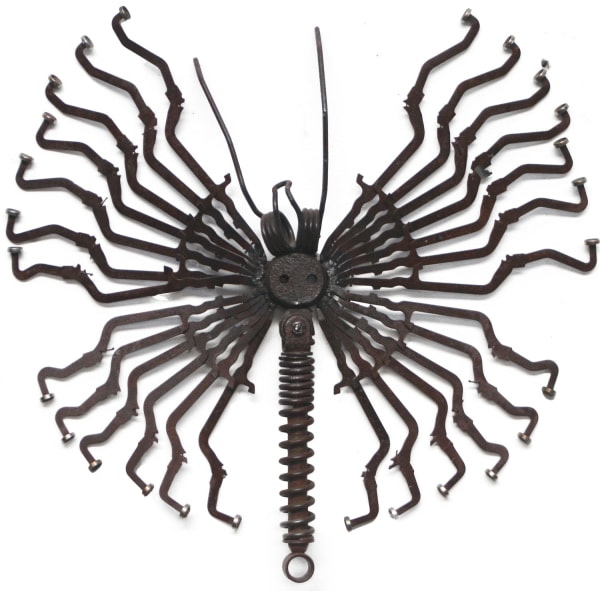

Helen DenerleyPlier Pollinator, 2023pliers, bike parts, motorbike spring, agricultral springs and brakeshoes107cm (h) x 104cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EPlier%20Pollinator%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Epliers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebike%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emotorbike%20spring%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eagricultral%20springs%20and%20brakeshoes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E107cm%20%28h%29%20x%20104cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyPlier Pollinator, 2023pliers, bike parts, motorbike spring, agricultral springs and brakeshoes107cm (h) x 104cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EPlier%20Pollinator%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Epliers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebike%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emotorbike%20spring%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eagricultral%20springs%20and%20brakeshoes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E107cm%20%28h%29%20x%20104cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBicycle Butterfly, 2022scrap metal120cm (h) x 137cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBicycle%20Butterfly%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2022%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%20137cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBicycle Butterfly, 2022scrap metal120cm (h) x 137cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBicycle%20Butterfly%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2022%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%20137cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySilent Moth, 2023silencer, dairy equipment, paraffin lamp and filter138cm x 74cm x 20cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESilent%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esilencer%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Edairy%20equipment%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eparaffin%20lamp%20and%20filter%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E138cm%20x%2074cm%20x%2020cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySilent Moth, 2023silencer, dairy equipment, paraffin lamp and filter138cm x 74cm x 20cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESilent%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esilencer%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Edairy%20equipment%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eparaffin%20lamp%20and%20filter%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E138cm%20x%2074cm%20x%2020cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpider 1, 2023bicycle forks and headlights70cm (h) x 180cm x 150cm£ 5,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpider%201%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebicycle%20forks%20and%20headlights%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E70cm%20%28h%29%20x%20180cm%20x%20150cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySpider 1, 2023bicycle forks and headlights70cm (h) x 180cm x 150cm£ 5,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpider%201%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebicycle%20forks%20and%20headlights%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E70cm%20%28h%29%20x%20180cm%20x%20150cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyKestrel i, 2023brake shoes, scaffold parts, trowels and garden shears27cm (h) x 43cm x 11cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etrowels%20and%20garden%20shears%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E27cm%20%28h%29%20x%2043cm%20x%2011cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyKestrel i, 2023brake shoes, scaffold parts, trowels and garden shears27cm (h) x 43cm x 11cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etrowels%20and%20garden%20shears%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E27cm%20%28h%29%20x%2043cm%20x%2011cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyKestrel ii, 2023brake shoes, scaffold parts, trowels and garden shears27cm (h) x 42cm x 11cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etrowels%20and%20garden%20shears%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E27cm%20%28h%29%20x%2042cm%20x%2011cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyKestrel ii, 2023brake shoes, scaffold parts, trowels and garden shears27cm (h) x 42cm x 11cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etrowels%20and%20garden%20shears%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E27cm%20%28h%29%20x%2042cm%20x%2011cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyChess Set - sparkplugs - with table and chairs, 2023spark plugsboard 46cm x 46cm

Helen DenerleyChess Set - sparkplugs - with table and chairs, 2023spark plugsboard 46cm x 46cm

king 10.5cm high£ 8,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EChess%20Set%20-%20sparkplugs%20-%20with%20table%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espark%20plugs%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eboard%2046cm%20x%2046cm%3Cbr/%3E%0Aking%2010.5cm%20high%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyChess Set - keys with table and chairs, 2023old keysboard 46cm x 46cm

Helen DenerleyChess Set - keys with table and chairs, 2023old keysboard 46cm x 46cm

king 16cm high£ 8,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EChess%20Set%20-%20keys%20with%20table%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eold%20keys%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eboard%2046cm%20x%2046cm%3Cbr/%3E%0Aking%2016cm%20high%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyTypewriter Moth, 2023typewriter keys and springs54cm (h) x 55cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ETypewriter%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Etypewriter%20keys%20and%20springs%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E54cm%20%28h%29%20x%2055cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyTypewriter Moth, 2023typewriter keys and springs54cm (h) x 55cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ETypewriter%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Etypewriter%20keys%20and%20springs%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E54cm%20%28h%29%20x%2055cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySnake, 2023steel pipe and scaffold clip10cm x 56cm x 34cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESnake%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20pipe%20and%20scaffold%20clip%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E10cm%20x%2056cm%20x%2034cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySnake, 2023steel pipe and scaffold clip10cm x 56cm x 34cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESnake%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20pipe%20and%20scaffold%20clip%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E10cm%20x%2056cm%20x%2034cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyRockfish26.5cm (h) x 16cm x 67cm£ 2,700.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERockfish%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E26.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%2016cm%20x%2067cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyRockfish26.5cm (h) x 16cm x 67cm£ 2,700.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERockfish%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E26.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%2016cm%20x%2067cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyStoatscrap metal45cm x 21cm x 7cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EStoat%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E45cm%20x%2021cm%20x%207cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyStoatscrap metal45cm x 21cm x 7cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EStoat%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E45cm%20x%2021cm%20x%207cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGolden Spider, 2023brass and spoons14cm (h) 33cm diameterSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGolden%20Spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrass%20and%20spoons%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E14cm%20%28h%29%2033cm%20diameter%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGolden Spider, 2023brass and spoons14cm (h) 33cm diameterSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGolden%20Spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrass%20and%20spoons%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E14cm%20%28h%29%2033cm%20diameter%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpring Moth, 2023agricultural and motorbike springs55cm (h) x 65cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpring%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20and%20motorbike%20springs%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E55cm%20%28h%29%20x%2065cm%20%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySpring Moth, 2023agricultural and motorbike springs55cm (h) x 65cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpring%20Moth%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20and%20motorbike%20springs%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E55cm%20%28h%29%20x%2065cm%20%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySwallows, 2023pliers, scaffold clips, scissors and brakeshoes22cm x 15cm x 54cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESwallows%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Epliers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20clips%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escissors%20and%20brakeshoes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E22cm%20x%2015cm%20x%2054cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySwallows, 2023pliers, scaffold clips, scissors and brakeshoes22cm x 15cm x 54cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESwallows%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Epliers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffold%20clips%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escissors%20and%20brakeshoes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E22cm%20x%2015cm%20x%2054cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBeetle Specimen Box, 2023teaspoons30cm x 22cm x 4.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBeetle%20Specimen%20Box%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eteaspoons%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2022cm%20x%204.5cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBeetle Specimen Box, 2023teaspoons30cm x 22cm x 4.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBeetle%20Specimen%20Box%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eteaspoons%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2022cm%20x%204.5cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyButterfly specimen box, 202345cm (h) x 31.5cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EButterfly%20specimen%20box%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E45cm%20%28h%29%20x%2031.5cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyButterfly specimen box, 202345cm (h) x 31.5cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EButterfly%20specimen%20box%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E45cm%20%28h%29%20x%2031.5cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyMagnetic Chess Set, 20237cm high king, 27cm x 27cm boardSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMagnetic%20Chess%20Set%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E7cm%20high%20king%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E27cm%20x%2027cm%20board%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyMagnetic Chess Set, 20237cm high king, 27cm x 27cm boardSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMagnetic%20Chess%20Set%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E7cm%20high%20king%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E27cm%20x%2027cm%20board%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLizard i, 2023steel and brass34cm x 18cm x 5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E34cm%20x%2018cm%20x%205cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyLizard i, 2023steel and brass34cm x 18cm x 5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E34cm%20x%2018cm%20x%205cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLizard ii, 2023steel and brass34cm x 18cm x 5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E34cm%20x%2018cm%20x%205cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyLizard ii, 2023steel and brass34cm x 18cm x 5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E34cm%20x%2018cm%20x%205cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyStarling ii, 2023Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EStarling%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyStarling ii, 2023Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EStarling%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023brake shoes, scissors, nails and shelf bracket22cm (h) x 30cm x 9cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESongthrush%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escissors%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Enails%20and%20shelf%20bracket%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E22cm%20%28h%29%20x%2030cm%20x%209cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023brake shoes, scissors, nails and shelf bracket22cm (h) x 30cm x 9cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESongthrush%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escissors%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Enails%20and%20shelf%20bracket%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E22cm%20%28h%29%20x%2030cm%20x%209cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBlackbird, 2023scissors, gear handles, brake shoes and scaffold clip.18cm (h) x 27cm x 8cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBlackbird%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escissors%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egear%20handles%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scaffold%20clip.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E18cm%20%28h%29%20x%2027cm%20x%208cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBlackbird, 2023scissors, gear handles, brake shoes and scaffold clip.18cm (h) x 27cm x 8cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBlackbird%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escissors%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egear%20handles%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scaffold%20clip.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E18cm%20%28h%29%20x%2027cm%20x%208cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySalvage, 2022scrap metal19cm (h) 28cm x 8cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESalvage%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2022%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E19cm%20%28h%29%2028cm%20x%208cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySalvage, 2022scrap metal19cm (h) 28cm x 8cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESalvage%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2022%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E19cm%20%28h%29%2028cm%20x%208cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyWee bird i, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyWee bird i, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyWee bird ii, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyWee bird ii, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyWee bird iii, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20iii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyWee bird iii, 202312cm (h) x 20cm x 6cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EWee%20bird%20iii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12cm%20%28h%29%20x%2020cm%20x%206cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Imp, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Imp%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Imp, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Imp%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Pacific Steamboat Navigation Company, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Pacific%20Steamboat%20Navigation%20Company%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Pacific Steamboat Navigation Company, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Pacific%20Steamboat%20Navigation%20Company%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Rolex, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Rolex%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleySpoon Bird - Rolex, 2023spoons and scrap8cm (h) x 15cm x 4cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpoon%20Bird%20-%20Rolex%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Espoons%20and%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E8cm%20%28h%29%20x%2015cm%20x%204cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBee i, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBee i, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBee ii, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBee ii, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBee iii, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20iii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyBee iii, 2023steel nuts and brass3.5cm (h) x 4cm x 3.5cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBee%20iii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Esteel%20nuts%20and%20brass%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.5cm%20%28h%29%20x%204cm%20x%203.5cm%3C/div%3E

-

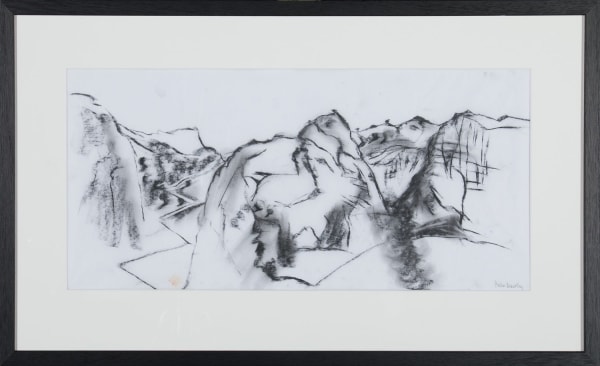

Helen DenerleyView from El Hacho i, 2023charcoal34cm x 54cm

Helen DenerleyView from El Hacho i, 2023charcoal34cm x 54cm

(45cm x 75cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EView%20from%20El%20Hacho%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Echarcoal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E34cm%20x%2054cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2845cm%20x%2075cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyView from El Hacho ii, 2023Charcoal30cm x 60cm

Helen DenerleyView from El Hacho ii, 2023Charcoal30cm x 60cm

(44cm x 65cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EView%20from%20El%20Hacho%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3ECharcoal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2060cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2844cm%20x%2065cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023charcoal73cm x 55cm

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023charcoal73cm x 55cm

(91cm x 72cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Echarcoal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E73cm%20x%2055cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2891cm%20x%2072cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

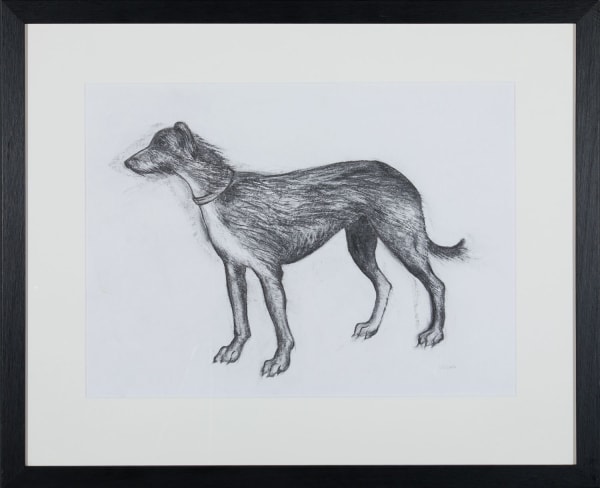

Helen DenerleyLurchercharcoal40cm x 54cm

Helen DenerleyLurchercharcoal40cm x 54cm

(76cm x 62cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELurcher%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Echarcoal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E40cm%20x%2054cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2876cm%20x%2062cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyOld Road to Ronda, 2023oil pastel and ink44cm x 40cm framedSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EOld%20Road%20to%20Ronda%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eoil%20pastel%20and%20ink%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E44cm%20x%2040cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyOld Road to Ronda, 2023oil pastel and ink44cm x 40cm framedSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EOld%20Road%20to%20Ronda%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eoil%20pastel%20and%20ink%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E44cm%20x%2040cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

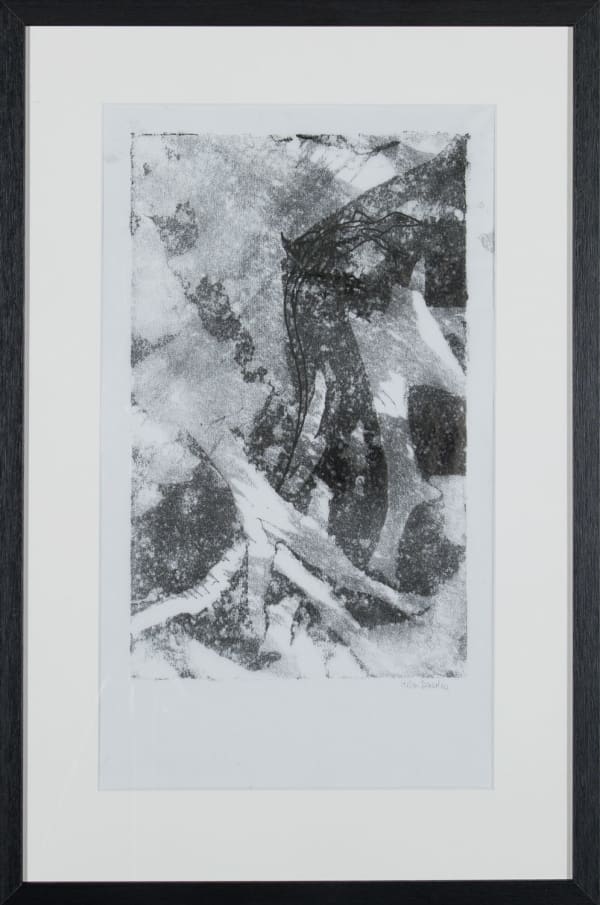

Helen DenerleyBeast on Hillside, 2023monoprint19cm x 29cm

Helen DenerleyBeast on Hillside, 2023monoprint19cm x 29cm

(37cm x 46cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBeast%20on%20Hillside%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E19cm%20x%2029cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2837cm%20x%2046cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023ink40cm x 24cm

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023ink40cm x 24cm

(58cm x 41cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eink%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E40cm%20x%2024cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2858cm%20x%2041cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESongthrush%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint39cm x 24cm

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint39cm x 24cm

85cn x 43cm framedSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESongthrush%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E39cm%20x%2024cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A85cn%20x%2043cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyChurch, Andalucia, 2023monoprint43cm x 30cm

Helen DenerleyChurch, Andalucia, 2023monoprint43cm x 30cm

(65cm x 43cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EChurch%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3EAndalucia%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E43cm%20x%2030cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2865cm%20x%2043cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLizard on a Rock, 2023monoprint20cm x 25cm

Helen DenerleyLizard on a Rock, 2023monoprint20cm x 25cm

42cm x 46cm framed%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20on%20a%20Rock%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E20cm%20x%2025cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A42cm%20x%2046cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGoat on a Hill, 2023monoprint19cm x 29cm

Helen DenerleyGoat on a Hill, 2023monoprint19cm x 29cm

(37cm x 46cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20on%20a%20Hill%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E19cm%20x%2029cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2837cm%20x%2046cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGhost Spider, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyGhost Spider, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyKestrel, 2023monoprint48cm x 34cm framedSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E48cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyKestrel, 2023monoprint48cm x 34cm framedSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EKestrel%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E48cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleySongthrush, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESongthrush%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBlackbird 1, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyBlackbird 1, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBlackbird%201%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBlackbird 2, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyBlackbird 2, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBlackbird%202%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGhost Kestrel, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyGhost Kestrel, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)Sold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Kestrel%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyBeetles, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyBeetles, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EBeetles%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyStarlings, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleyStarlings, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EStarlings%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia, 2023monoprint19cm x 22cm

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia, 2023monoprint19cm x 22cm

37cm x 38cm framed%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Church%20in%20Andalucia%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E19cm%20x%2022cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A37cm%20x%2038cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia ii, 2023monoprint40cm x 25cm

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia ii, 2023monoprint40cm x 25cm

(65cm x 43cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Church%20in%20Andalucia%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E40cm%20x%2025cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2865cm%20x%2043cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLizard on rock i, 2023monoprint39cm x 24cm

Helen DenerleyLizard on rock i, 2023monoprint39cm x 24cm

(85cm x 43cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20on%20rock%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E39cm%20x%2024cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2885cm%20x%2043cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyLizard on rock ii, 2023monoprint40cm x 24.5cm

Helen DenerleyLizard on rock ii, 2023monoprint40cm x 24.5cm

(62cm x 45cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELizard%20on%20rock%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E40cm%20x%2024.5cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2862cm%20x%2045cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia ii, 2023monoprint37cm x 39cm framed%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Church%20in%20Andalucia%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E37cm%20x%2039cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGhost Church in Andalucia ii, 2023monoprint37cm x 39cm framed%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGhost%20Church%20in%20Andalucia%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E37cm%20x%2039cm%20framed%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleySpider, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

Helen DenerleySpider, 2023monoprint30cm x 15cm

(48cm x 34cm framed)%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ESpider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emonoprint%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E30cm%20x%2015cm%3Cbr/%3E%0A%2848cm%20x%2034cm%20framed%29%3C/div%3E

-

Helen DenerleyInfinity Column, 2023fire extinguishers and boiler expansion tanks6.5m high%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EInfinity%20Column%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Efire%20extinguishers%20and%20boiler%20expansion%20tanks%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E6.5m%20high%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyInfinity Column, 2023fire extinguishers and boiler expansion tanks6.5m high%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EInfinity%20Column%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Efire%20extinguishers%20and%20boiler%20expansion%20tanks%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E6.5m%20high%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyGiant spider, 2023combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high£ 33,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGiant%20spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecombine%20harvester%20dividers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egas%20guns%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etanks%20and%20barbeque%20lid%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.3m%20high%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGiant spider, 2023combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high£ 33,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGiant%20spider%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Ecombine%20harvester%20dividers%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Egas%20guns%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etanks%20and%20barbeque%20lid%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E3.3m%20high%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyMale orangutan, 2023120cm (h) x 90cm x 45cmold British motorbikes, tilly lamp and scaffold parts£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMale%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%2090cm%20x%2045cm%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbikes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etilly%20lamp%20and%20scaffold%20parts%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyMale orangutan, 2023120cm (h) x 90cm x 45cmold British motorbikes, tilly lamp and scaffold parts£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMale%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3E120cm%20%28h%29%20x%2090cm%20x%2045cm%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbikes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etilly%20lamp%20and%20scaffold%20parts%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyMother and baby orangutan, 2023old British motorbike frames, brake shoes, scaffolding parts, bolts, bells.66cm (h) x 114cm x 74cm£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMother%20and%20baby%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbike%20frames%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebolts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebells.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E66cm%20%28h%29%20x%20114cm%20x%2074cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyMother and baby orangutan, 2023old British motorbike frames, brake shoes, scaffolding parts, bolts, bells.66cm (h) x 114cm x 74cm£ 16,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EMother%20and%20baby%20orangutan%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eold%20British%20motorbike%20frames%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Escaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebolts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebells.%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E66cm%20%28h%29%20x%20114cm%20x%2074cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyHaiku sphere, 2023mild-steel rod100cm x 100cm x 100cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EHaiku%20sphere%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emild-steel%20rod%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E100cm%20x%20100cm%20x%20100cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyHaiku sphere, 2023mild-steel rod100cm x 100cm x 100cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EHaiku%20sphere%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Emild-steel%20rod%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E100cm%20x%20100cm%20x%20100cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyGoat i, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers73cm (h) x 103cm x 32cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E73cm%20%28h%29%20x%20103cm%20x%2032cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGoat i, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers73cm (h) x 103cm x 32cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20i%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E73cm%20%28h%29%20x%20103cm%20x%2032cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyGoat ii, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers72cm (h) x 111cm x 38cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E72cm%20%28h%29%20x%20111cm%20x%2038cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyGoat ii, 2023agricultural scrap, bicycle and scaffolding parts, hammers72cm (h) x 111cm x 38cm%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EGoat%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20scrap%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebicycle%20and%20scaffolding%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ehammers%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E72cm%20%28h%29%20x%20111cm%20x%2038cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyFound object chess set, table and chairs, 2023drills, meat-grinders and agricultural scrapKing 47cm high, board 120cm x 120cm£ 15,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EFound%20object%20chess%20set%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etable%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Edrills%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emeat-grinders%20and%20agricultural%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3EKing%2047cm%20high%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eboard%20120cm%20x%20120cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyFound object chess set, table and chairs, 2023drills, meat-grinders and agricultural scrapKing 47cm high, board 120cm x 120cm£ 15,000.00%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3EFound%20object%20chess%20set%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Etable%20and%20chairs%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Edrills%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Emeat-grinders%20and%20agricultural%20scrap%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3EKing%2047cm%20high%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Eboard%20120cm%20x%20120cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyLurcher ii, 2019scrap metal133cm x 72cm (h) x 25cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELurcher%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2019%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E133cm%20x%2072cm%20%28h%29%20x%2025cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyLurcher ii, 2019scrap metal133cm x 72cm (h) x 25cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ELurcher%20ii%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2019%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Escrap%20metal%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E133cm%20x%2072cm%20%28h%29%20x%2025cm%3C/div%3E -

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023agricultural parts, brake shoes and scythes110cm (h) x 143cm x 69cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scythes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E110cm%20%28h%29%20x%20143cm%20x%2069cm%3C/div%3E

Helen DenerleyRed Kite, 2023agricultural parts, brake shoes and scythes110cm (h) x 143cm x 69cmSold%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EHelen%20Denerley%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ERed%20Kite%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E2023%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3Eagricultural%20parts%3Cspan%20class%3D%22comma%22%3E%2C%20%3C/span%3Ebrake%20shoes%20and%20scythes%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E110cm%20%28h%29%20x%20143cm%20x%2069cm%3C/div%3E -